3 WAVES

The opioid epidemic has occurred in three waves. The first wave began in 1991 when deaths involving opioids began to rise following a sharp increase in the prescribing of opioid and opioid-combination medications for the treatment of pain. The increase in opioid prescriptions was influenced by reassurances given to prescribers by pharmaceutical companies and medical societies claiming that the risk of addiction to prescription opioids was very low.

The second wave of the opioid epidemic started around 2010 with a rapid increase in deaths from heroin abuse. As early efforts to decrease opioid prescribing began to take effect, making prescription opioids harder to obtain, the focus turned to heroin, a cheap, widely available, and potent illegal opioid.

The third wave of the epidemic began in 2013 as an increase in deaths related to synthetic opioids like fentanyl. The sharpest rise in drug-related deaths occurred in 2016 with over 20,000 deaths from fentanyl and related drugs.

The current opioid crisis ranks as one of the most devastating public health catastrophes of our time. It started in the mid-1990s when OxyContin, promoted by Purdue Pharma and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), triggered the first wave of deaths linked to use of legal prescription opioids. Then came a second wave of deaths from a heroin market that expanded to attract already addicted people. More recently, a third wave of deaths has arisen from illegal synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Millions more are affected by related problems involving homelessness, joblessness, truancy, and family disruption.

How many of these deaths, these suffering Americans, would be alive and well today were it not for the insufferable greed and arrogance of this irresponsible family? Regardless of what Arthur Sackler and his brothers say about how this devil drug is helping people in pain, there is no justification on continuing its production once it became known how dangerous it was.

The plan for the profitable pain relief by death

-

The company spent $207 million on the launch, doubling its sales force to 600, according to a court declaration. Sales reps pitched the drug to family doctors and general practitioners to treat common conditions such as back aches and knee pain. Their hook was the convenience of twice-a-day dosing.

With Percocet and other short-acting drugs, patients have to remember to take a pill up to six times a day, Purdue told doctors. OxyContin “spares patients from anxious ‘clockwatching,’” a 1996 news release said

-

The FDA label suggested Purdue Pharma had created a superior product in OxyContin, declaring that its “delayed absorption” was “believed to reduce” the opioid’s abuse.

It was the first opioid to win that stamp of approval from the FDA, despite the fact there was no testing to back up that conclusion, nor was there any proof for the label’s conclusion that “ ‘addiction’ to opioids legitimately used in the management of pain is very rare.”

-

Purdue relied on the concept of pseudo-addiction, a counterintuitive theory that argued higher doses of opioids could actually prevent addiction.

If the patient’s motivation for seeking opioids was pain, that meant they were not addicted but “pseudo-addicted”, the argument went. Patients with inadequately treated pain might exhibit symptoms of addiction, but the best way to treat those symptoms and prevent addiction was to increase their opioid dose

-

Lawsuits were resisted by Purdue, defending by saying addiction was the problem of the abuser not the drug.

Johnson N Johnson Tasmanian Opioid Island

NOT that long ago, Tasmania’s opium poppy industry was widely lauded for the economic boost it offered the island state.

The poppies not only offered farmers a far more lucrative crop than potatoes, they were also being used in the production of medicines that could provide much needed relief to suffering patients – or at least so the story went.

As recently as 2015, the New York Times published an article about Australia’s “Opium Island”, where pretty much the biggest challenges the industry faced were a state ban on genetic engineering and the predation of wallabies, “close relatives of kangaroos”.

Stoned wallabies “can become disoriented and lose their ability to find water”, a pharmaceutical company supply manager told the Times.

Six years on, it’s hard to imagine a major news organisation writing about the poppy fields without mentioning the wallaby in the room: opioid addiction.

What is Addiction?

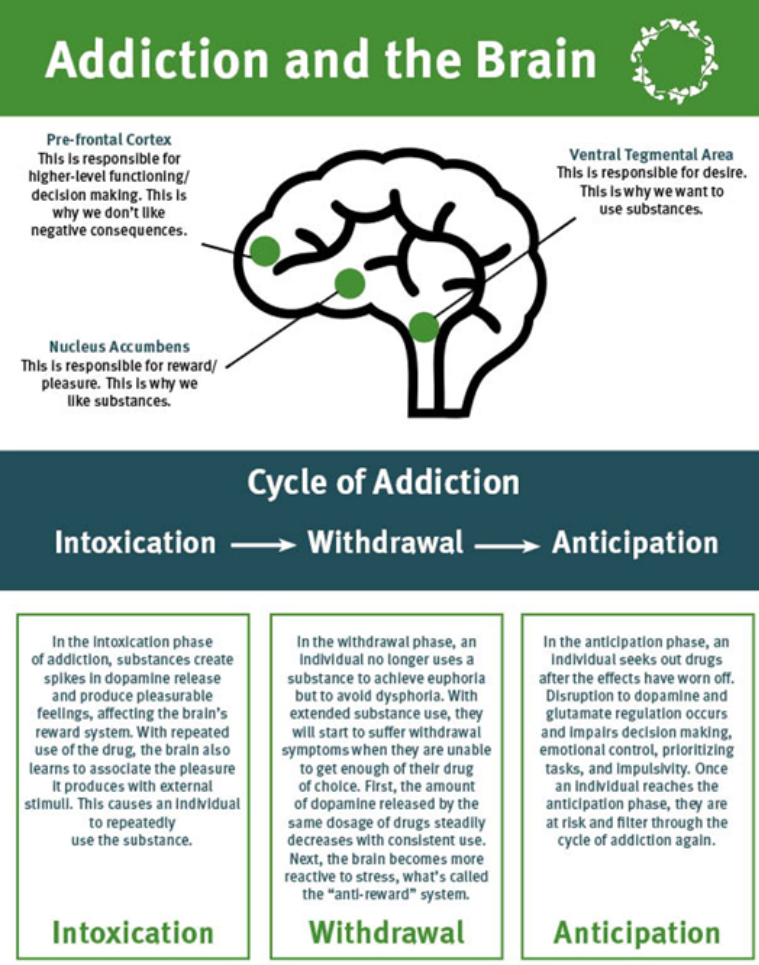

When someone uses a substance, whether for recreational purposes, to self-medicate a mood disorder, or control pain after a surgery or injury, they often experience a euphoric or relaxing effect. This pleasurable response registers in the brain’s reward system as a positive, desirable experience. The memory of this experience then motivates the person to repeat it.

Chemistry of Withdrawal

When opioids are first taken, a stress-associated region of the brain called the locus coeruleus gets quieted. But after long-term exposure, the brain compensates by supercharging the neurons in that region. If the dampening effects of opioids are taken away, an altered locus coeruleus can wreak havoc on the body, producing the agonizing symptoms of withdrawal

How addiction occurs

Anyone who takes opioids is at risk of developing addiction. Your personal history and the length of time you use opioids play a role, but it's impossible to predict who's vulnerable to eventual dependence on and abuse of these drugs. Legal or illegal, stolen and shared, these drugs are responsible for the majority of overdose deaths in the U.S. today.

Addiction is a condition in which something that started as pleasurable now feels like something you can't live without. Doctors define drug addiction as an irresistible craving for a drug, out-of-control and compulsive use of the drug, and continued use of the drug despite repeated, harmful consequences. Opioids are highly addictive, in large part because they activate powerful reward centers in your brain.